Ibne Safi goes

international, again. In a way he was always international since his

books used to be published simultaneously in both Pakistan and India.

Yet his work was not available in English. Random House India has now

made available Safi’s Imran Series translated into English by Bilal

Tanweer. Titled The House of Fear, the collected volume containing the

first two novels is already out. Blaft Publications is soon to publish

some novels of Jasoosi Duniya translated by the renowned Shamsur Rehman

Faruqui.

The Hindi editions, meanwhile,

are being published by Harper Collins, India. Unlike the earlier Hindi

versions of the 1950s and 60s, the names of the heroes Ahmad Kamal

Faridi and Ali Imran have not been changed to Vinod and Rajesh. Perhaps

this is the right moment to reconsider how much was lost when society

failed to locate Safi’s work in the context of the early years of

independence.

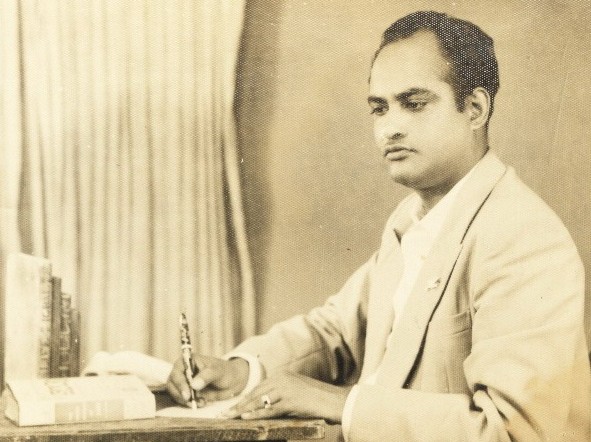

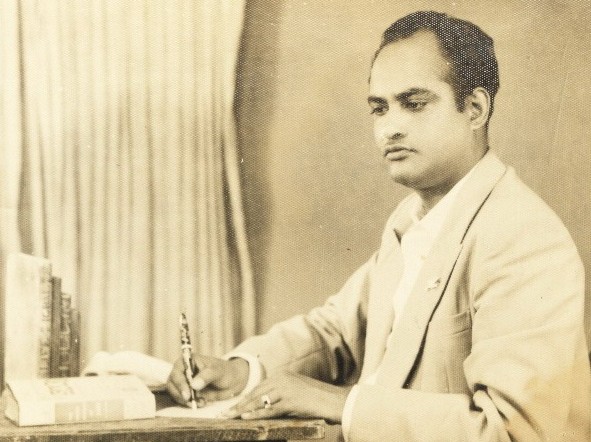

The author was born Asrar Ahmad

in April 1928 in Nara, a small town near Allahabad. One of the earliest

influences on him was Tilism-i-Hoshruba, the gigantic Urdu classic

(currently being translated into English with the first volume already

available). The next most important influence was Rider Haggard, whose

novels She and The Return of She he read soon after moving to Allahabad

for higher education.

When Safi started writing

fiction and poetry he followed the literary trends of those days, for

example the Progressive Writers’ Movement, but became disillusioned with

them some time around 1942.

It seems that he had come to

believe that purely speculative theories did not provide a very sound

basis for collective development of societies – at least that is the

impression one gets from his autobiographical essays such as ‘Mien Nay

Likhna Kaisay Shuroo Kiya’ (‘How Did I Start Writing’) and ‘Baqalam Khud’

(‘In My Own Hand’). However, he kept the company of the leading

progressive writers for as long as he stayed in India, which was till

August 1952.

The catastrophic pillage and

massacre of 1947 confirmed, at least to him, his doubts about the

ability of pure speculation to prevent social tragedies. ‘I kept

thinking and thinking, and arrived at the conclusion that such things

will keep happening until the human being learns to respect the law,’ he

later wrote.

In the later part of 1951 a

comment made by someone to the effect that only sexual stuff could sell

in Urdu provoked Asrar to launch a movement against the contemporary

trends of high literature. He picked up Ironsides’ Lone Hand, a

detective story by Victor Gunn and adapted it according to the tastes of

the Urdu reading public, adding some literary flavour of his own and

remodeling the two main characters to represent his ideals.

Dilair Mujrim which was

published by Nakhat Publications in Allahabad and distributed by A.H.

Wheeler & Co. in March 1952 sold like hot cakes.

Asrar Ahmad, who had by then

adopted the pen name ‘Ibne Safi’ (‘the Son of Safi’, since Safiullah was

the name of his father) had proven his point.

He migrated to Pakistan in

August the same year and spent the rest of his life in Karachi. By the

time he died on July 26, 1980 he had written 240 mystery novels based on

the stock characters Faridi, Hameed and Ali Imran. By his own account,

except for eight adaptations, all of them were based on original plots

and almost all were published simultaneously in Allahabad and Karachi

since the author remained equally popular on both sides of the border.

Literary critics labeled Safi a

mere ‘popular writer’ and his fiction as ‘pulp’. This overlooks the fact

that writers of pulp fiction seldom have explicitly reformist agendas

(Ian Fleming once justified the promiscuity of James Bond by saying

something to the effect that he was catering to an age where courtship

was being replaced with seduction).

Not so with Safi. He was

reinforcing the messages of commonly respected reformers such as Sir

Syed Ahmad Khan, the Ali Brothers and Allama Iqbal, while, ironically,

the writers of ‘high literature’ were trying to outdo each other in

selling sex and sadism. Also, the works of Safi touched upon a wider

range of contemporary issues – and his literary allusions covered a more

diverse range of art, literature and philosophy – than any other writer

who ever wrote fiction in Urdu.

These happen to be a few of the

issues that were brushed under the carpet by gatekeepers of literary

establishments long ago. More issues can be raised, and they are very

likely to be raised now that interest in the work of Safi is about to

scale new heights.

Online information about the

life and works of Ibne Safi can be found at

www.ibnesafi.info and

www.wadi-e-urdu.com, both non-profit

websites supported by his family, which also maintains a Facebook page

at

http://www.facebook.com/ibnesafi.

http://www.dawn.com/2010/12/05/profile-from-pakistan-with-love.html